- Home

- Erin Saldin

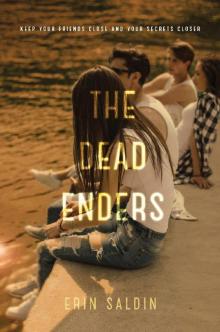

The Dead Enders

The Dead Enders Read online

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

* * *

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

For Sylvie and Frankie

GOLD FORK IS . . .

But first, let me tell you what it isn’t. This is not a fantasy. It’s not even a love story. There will be no dragons, no spells, no visitors from worlds that look like ours but aren’t, quite. There won’t even be time travel. No one is carried away on an asteroid. No one’s ancestors appear in a nimbus mist to hand over the key to the forgotten city. There will be no castle storming. We just aren’t that lucky.

Or maybe we are. Maybe it is a fantasy, after all. Maybe—yes, definitely—this is a love story. But it’s not the story you’d expect. It never is, in Gold Fork.

DAVIS

It’s a regular firestorm of paper. I catch sight of some grades on the loose sheets as they float past me in the hall: C+, B, A–, a hastily scratched Rewrite for credit. The floor is carpeted with what we don’t want. The janitors hate us. I make my way to my locker, listening to the shouting and the heavy clang of a couple hundred metal doors swinging shut for the summer. I’m trying hard not to look for Jane, but every time I see a corner of blue—blue shirt, blue skirt, even someone’s blue backpack—I think it’s her, and my breath catches in my throat.

It’s never her.

Georgie’s leaning against my locker door in jeans and some obscure band T-shirt. She looks like she belongs on one of those black-and-white movie posters, straight out of French cinema. Like she really should have a cigarette in her hand. She raises one hand in a lazy wave as if she hasn’t actually been waiting for me.

“Georgie,” I say, “don’t take this the wrong way, but you really make the rest of us look bad. Just become famous already and let us all excel at normality.”

She kicks a heel against the locker, pushing off. “I like your brand of bullshit, Davis.” Then she looks around. “Where are the others?”

I shrug. “Ana was in pre-calc with me this morning, but I haven’t seen her since.”

“What about Erik?”

“You know we don’t have any of the same classes.” I don’t have to say it, but she has to know what I’m thinking: I never see Erik at school—or if I do, we don’t talk much. The only place our lives intersect is the Den.

“Bet he’s forgotten,” she says. “Of course.”

My phone buzzes with a text just as Ana appears at the end of the hall, her head moving in a slow swivel until she sees us. She weaves through the crowd. Her hair is messy, and even from here I can see the ink smudge that’s perpetually on her cheek—one of the drawbacks of being left-handed and using cheap pens.

I read the text just as she says, “Well, we made it. Last day of school.”

“You guys,” I say, and hold up my phone. I squint at it like I can’t read the words, but I can. I can read them perfectly.

“A week’s reprieve before the Weekenders get here,” says Georgie. “I’ll be spending it on my bed, asleep.”

“You guys.”

“I’ll probably just try to see more of Vera,” says Ana.

“How’s she doing, anyway?” Georgie asks.

“She’s—” Ana starts to say, but she stops when I grab her hand. I stare at it for a moment before letting go.

“You. Guys.” I take a breath. “Dan just texted me from the newspaper office. The Nelson cabin burned down last night.”

They don’t say anything for a minute. The whole hallway freezes, it seems—if this were a movie, I’d swear even the papers stop flying halfway through the air. No one else can hear us, but still. It’s a collective breath, held.

Then we let it out.

“Shit!” Georgie’s face gets red. “No. No fucking way.”

“It burned. To the ground.” I look at my phone. “Foundation and fireplace are the only things left.”

Georgie kicks the locker, hard, with the toe of her combat boot. “Shit!” She covers her face with her hands.

“Are you okay?” asks Ana, even though we should be asking her that. She pulls her sleeve down over her left arm, covering the silver scar that winds—I know, I’ve seen it before, saw it even when it wasn’t a scar yet and was just blood—from her elbow to her wrist, carving a line through her skin.

Georgie looks up and takes a deep breath. “Fine. Fuck. I’m fine.” Then she adds, “It shouldn’t have burned. That thing was made of steel.” Her voice is still a little shaky. “I just—I’m sorry. But there wasn’t any fuel around it. I mean, we took care of that.”

We took care of that.

She’s right, of course. When the chapel burned to the ground two years ago, there was nothing left on that plot of land but soot and char.

“The Nelsons never should have built their cabin there,” I say. “Hallowed ground and all that. Maybe no one started this fire. Maybe it was just karma. Maybe it’s just the universe saying, If you can’t keep a chapel from burning down here, you can’t have anything.” I’m trying to make light of it, but really, I’m just thinking of my mom and wondering if I should text her. The chapel fire is more than a memory to her. It’s a haunting.

• • •

You know how people say, “I remember it like it was yesterday”? I’ve always thought that was so misguided. I mean, can anyone really remember yesterday accurately? Once the screen of sleep has fallen, events start to warp, take on different tones, different meanings. By the time we wake up the next day, yesterday might as well be last year.

But the chapel fire? I remember most of it like it’s right now. And I always will.

• • •

Creeping out of my one-man tent at midnight, a feeling like rising water in my gut. Excitement. Nervousness. Georgie’s voice still ringing in my head from after the cookout: “Meet in the chapel later?” Georgie, whom I hardly know except to know not to fuck with her. “Ana will be there.”

Silently passing the other tents, some big, some small. I skirt my mom’s tent—our fearless leader. The whole church youth group is here. Most of them are asleep. Not all of them have been chosen.

The chapel rises out of the dark, woods all around it, the cliffs beyond. When I enter, shutting the door quietly behind me, the air smells of incense and pine and dust. It’s dark, but I turn my headlamp on and look around. Ana’s standing with her arms wrapped around herself. She smiles, and the water rises another inch. Georgie says, “Good. You’re here.” And then Erik, looking as surprised to see me as I am to see him. I didn’t know whom to expect, but Erik-the-track-star? Erik-the-guy-who-doesn’t-need-this-because-he-already-has-everything-he-needs—girls-and-trophies-and-the-adoration-of-the-whole-damn-town? But here he is anyway. We nod at each other, two aliens whose ships have crashed on the same foreign planet.

I move next to Ana, and we bump shoulders in greeting. Then Georgie says, “A campfire’s not a campfire without a little smoke,” and she pulls from her pocket a perfectly rolled joint. Ana raises her eyebrows, and Erik says, “Thanks be to God.”

It’s my first time smoking, and I don’t want anyone to know. But once I see Ana coughing and sputtering after her hit, I start laughing because of course. Only Georgie and Erik know what they’re doing. Slowly—slowly—we relax. Make jokes, even. Georgie imitates Erik’s expression as he inhales, and he laughs. Ana and I lean against each other, comfortable finally. I’ll kiss her ton

ight, I know.

Everything is possible.

• • •

And that’s where it becomes memory again. Because everything was possible in that moment. But then the moment after happened, and the moment after that. And by the end of the night, what brought us together wasn’t the spark of new friendship and a cresting wave of maybe-finally-utterly-now. All of that was gone. What brought us together—joined us for the rest of our time in Gold Fork—were screams and sirens and blood and ash.

ANA

“It doesn’t make sense,” Georgie’s saying. “It just doesn’t make any sense.”

The noise around us is what I imagine the ocean sounds like: hollow and demanding. I look to my left to see if anyone’s listening, but all I see are faces open in exclamation and relief. Then everything dulls and becomes blurry as Chrissy Nolls walks by, the collar of her thin jacket turned up around her neck. Even so, I can still see the way the skin folds over itself in strange ridges along the back of her hairline, a misshapen landscape.

I glance at Davis and Georgie to see if they’ve noticed her. They have. Davis is holding his phone so tightly that I can see the whites of his knuckles. I think about reaching over, touching his hand, and banish the thought just as quickly.

“Oh God,” says Georgie. She closes her eyes for a long second. When she opens them again, Chrissy’s at the other end of the hall. Georgie looks at me quickly and then turns to Davis. “They got out, right? The Nelsons.”

His eyes follow Chrissy as she turns toward Tri High’s main doors and disappears into summer. He clears his throat. “Weren’t even there,” he says, checking his phone again. “The structure’s gone. That’s it.”

We all look in the direction Chrissy walked. “Good,” I say, and we all take a breath as the panic subsides.

“Copycat?” asks Georgie.

“Who would copy us?” I say. “Besides, the chapel was two years ago.”

“You’re right,” she says.

Davis takes a deep breath. “Two years ago today.”

“Shit,” says Georgie, and she’s patting her pockets, searching for something. I can guess what. She pulls out a lighter, flicks it once. “I need to smoke.” Then she adds, “Where’s Erik? Where the fuck is he?” Georgie is usually cooler than this. Nothing fazes her. It’s one of the things I admire about her. But she seems more rattled than I am, and frankly, I’m the one who should be crawling out of my skin. I touch my left arm with my right hand and breathe.

“Maybe he forgot,” says Davis. “He’s got his good-byes to deal with.”

“Not like anyone is going anywhere,” says Georgie. “Your girls will still be here all summer.”

A guy—soccer player, I should know his name but don’t—walks by, slapping Georgie on the shoulder. “See you at Fellman’s?” he asks.

“Better believe it,” she says.

“Good,” he says, and laughs. “We’ll party.” He walks off, yelling at someone down the hall about grab the wheels or something.

Most people in this school speak a language I don’t understand. And I don’t mean English; my mom may still retain some of the Spanish she grew up with, but she hasn’t passed it on to me. I wish she had. I wish I knew what it was like to dream in another language. To have private conversations with my mom in the grocery store that we can be fairly sure no one else comprehends. To still belong to the world she ran away from.

No, for better or for worse, English is my first (and only) language. But the language of my school is more complex, more riddled with double meanings and hidden jokes. Even Erik can sometimes feel as foreign to me as the football players, the snowmobilers, the kids who go hunting every weekend in the fall with their whole families. I look at Davis and Georgie, my closest friends in this town besides Vera. And I feel, like I’ve felt a thousand times since that night exactly two years ago, the particular pain of owing everything good in my life to that terrible fire.

• • •

I don’t know why Georgie invited me. But I’m not going to ask. I’ve watched her in youth group meetings—her easy way, her quick retorts. She’s never had time for me until now, and the doubt I’d normally feel is eclipsed by the bright spark of pleasure when she asks if I want to meet in the chapel to smoke later. “Davis will be there,” she says, and I wonder how she knows. Is my desire so clear? Can he see it too?

And then we’re smoking, and it’s easy. Davis, Georgie, and Erik—whom I don’t know well but who seems, in this space, to be funny and friendly in a way I’ve never thought he could be. The moon, bright through the chapel’s stained-glass windows, reflects off their faces so that they seem lit from within. Almost holy. And isn’t that what friendship is? And isn’t that what I’ve wanted for so long?

When we leave the chapel, the night is a quiet animal. We don’t know what we’ve done.

Until we do. Erik first: a quiet “Oh.” We turn around, and the cross on the door is burning, the chapel’s windows filling with smoke. Georgie’s voice: “Oh shit!” Davis’s: “Ana! Come back!” But I’ve heard the other sound—a quiet crying, a desperate mewling. And I remember the cat, curled in the corner of a pew with her kittens. I’m already heading back in.

GEORGIE

“Looks like you’ll be busy,” says Davis, watching Chris (soccer player, kind of dumb, eight ball once a month) walk away.

“No rest for the wicked,” I say, but I want to scream instead. You don’t even know! I want to shout in their faces. You don’t even know what’s at stake here! But I add, voice totally calm, “Fellman’s should be good for business.”

It has to be.

“The Weekenders will all be here by then,” says Ana, her expression a little wistful. She reaches over and pats a locker. “Good-bye, Gold Fork.”

“Hello, resort town,” says Davis. “Get ready for the costume change.”

I look down the hall. It’s almost cleared out by now. Most kids can’t get out of Tri High fast enough at the end of the year. But I know what they’re running toward, and it can wait.

“I don’t think Erik’s coming,” I say. I look around once more, as though he’s going to magically appear, sigh, and shake my head. Classic Erik. Always doing his own fucking thing. “I’ll text him and tell him to just meet us at the Den.”

“He wasn’t in English this morning,” says Ana. “I haven’t seen him around.”

“Bold move, missing the last day of school,” says Davis.

“Yeah,” I say, though I’m not surprised. The things Erik gets away with.

We head toward the big double doors. I inhale, letting the scent of old cafeteria food, rubber, and sweat wash over me. This is what I smell nine months of the year. This is what Gold Fork is, until it isn’t. Davis is right: In a week, it’ll all be replaced with newer smells. Better smells. The beautiful stench of wealth.

Those straight-to-DVD movies about gangsters or bank robbers? The ones where someone inevitably holds a wad of hundreds in front of his face, fans them and inhales, saying something stupid like “God, how I love the smell of money”? Those are bullshit.

You know what money smells like? Expensive tanning lotions and the exhaust of new speedboats. Lip gloss with the slightest hint of pomegranate or coconut, but not in an overpowering, corn syrupy, drugstore sort of way. Sunshine and possibility. That’s what money smells like. For the Weekenders, at least.

It smells different to me, but not by much. Because summer is the best season for business. Always has been. That is, unless you stupidly hid your stash—the one you expected to sell at Fellman’s—under the deck at the Nelsons’ cabin, knowing they were out of town. Unless a couple thousand dollars’ worth of drugs just burned up—incinerated, gone—in an instant. Unless you screwed yourself so royally that this summer has turned from a fun ride around the lake—one last round—into a mad scramble for money and lost time.

So maybe Davis is right. Maybe the Nelson fire is karma. And who better to point the cosmic finger at than

me?

• • •

Watching them around the campfire: Davis, singing along to his mom’s songs: “Jesus-Light,” she calls them. Trying his best to look like he doesn’t care, to not stare at Ana where she sits, hugging herself in the cold. She glances at him once or twice, but never when he’s looking. Erik, scuffing the toe of his running shoe in the dirt, mouthing the words because no way in hell he’s going to get caught with a song in his throat. A girl on each side of him. He looks at me and winks, everything already an inside joke between us, even the girls. Davis, Ana, Erik. I watch the three of them. I choose them carefully: the nerd, the nobody, the athlete. Not the friends a dealer would have. And so: the perfect cover.

And later: the cool of the night. The way the chapel envelops us as we smoke.

I like them more than I thought I would.

And even later: my shoe, grinding the joint against the floor of the chapel. Ana bending to pick it up and throw it away. Me saying, “Let’s leave it. Let your mom wonder who the sinners are, Davis.” Not knowing how right I am.

Only one sinner. Me.

ERIK

So I missed it. So what? Nothing happens on the last day anyway.

Here’s what I missed: the sound of two hundred stampeding animals as they flee their prison and make for the light. Getting my grade for the Algebra II final I took last week. Fending them off—all of them—as they ask what I’m doing after.

After what?

That’s the question.

When I get to the Den, hiding my bike in the bushes beside the lake road and climbing over the estate’s wrought-iron gate, they’re already waiting on the deck behind the big house, sitting comfortably in old Adirondack chairs that wouldn’t have been dusted in decades if it weren’t for us. They’re all looking out at the lake, but they turn when they hear my tennis shoes on the deck’s old wooden boards.

Ana and Davis raise their hands in greeting, but:

“What the hell, Erik,” says Georgie, narrowing her eyes. “We waited forever at school.”

The Dead Enders

The Dead Enders